It’s the self-help topic du jour: achieving “work/life" balance.

Tips for reaching this coveted state-of-being range from the physical (like exercising and unplugging from technology) to the psychological (like meditating and mentally “disconnecting” from work) to the sociological (like meticulously scheduling all of your outside-of-work interactions/activities with friends and family).

Don’t get me wrong: Many of these tips can be helpful. Implementing them could yield you a happier, more fulfilling life – both in terms of your work life and your life … life.

But you see, this is where the terminology gets confusing. “Work/life" balance implies that your work (your job or your career) and your life (your being or your existence) are on par with each other.

“The problem with work-life balance is that it suggests there is a trade-off – that one side must be ‘up’ and the other one ‘down,’ like a weighing scale that has two sides to it,” Jappreet Sethi, CEO of Ideak Katalyst, wrote on LinkedIn in June of 2014.

He continued, “Using the word ‘balance’ suggests that the two aspects are completely separate from one another and are at odds, that when you are at work you’re not really living.”

To be sure, this is by no means a novel criticism of the concept. In fact, at HubSpot, we often encourage “work/life” balance in employees. The goal of this article is to dive into the terminology, uncover the challenges, and explore the way in which the concept shapes our experiences.

A Matter of Semantics

Of course, many of us don’t interpret the “life” in “work/life" balance to mean our actual lives; what we really mean is our lifestyles, our leisure time. And that’s precisely what the concept used to be called: work/leisure balance.

Up until the 1980s, nobody talked about “work/life" balance, they talked about “work/leisure balance.“ And that concept – balancing work and leisure – goes back to the days of Plato and Aristotle. (More on that later.)

So, why the change in terminology? And if we really mean “lifestyle” nowadays when we’re talking about "work/life” balance, why don’t we say “lifestyle.” Are we that lazy that we need to shorten it? (I mean, I know I am that lazy. But I can’t speak for everyone.)

Semantics aside, the notion of “work/life” balance is confounding (and potentially detrimental) on a number of other levels.

As Boris Groysberg and Robin Abrahams noted in the March 2014 issue of the Harvard Business Review: “Work/life" balance is at best an elusive ideal and at worst a complete myth, today’s senior executives will tell you.“

So, could striving for some imaginary, idealistic sense of balance end up having negative repercussions on your life? That’s what we’ll be exploring in the paragraphs to come.

But first, I want to take a step back and review the history and etymology of “work/life” balance. We’ve glanced over this briefly already, but having a better understanding of how the concept (and terminology) has evolved over time will help us to better evaluate its modern incarnation.

The History of “Work/Life” Balance

15,000 B.C.

There are no jobs … at least not in the usual sense of the word. But there is still work – people must hunt, forage, and fish for food in order to survive. (And of course, they must take care of their children in order to ensure the survival of the species.)

Despite their lack of technology (or perhaps, because of it), our hunter/gatherer ancestors probably spent fewer hours working than we do today, and spent more time on things like music, art, storytelling, and getting busy in the bedroom … or cave, or whatever.

It’s also unclear whether our ancestors actually made a distinction between work and leisure. For them, it probably all just fell under the umbrella of “life.“

12,000-10,000 B.C.

The First Agricultural Revolution, also known as the Neolithic Revolution, made it possible for many of our foraging forbearers to settle down. Growing crops and raising livestock assured a steady food supply, which meant people didn’t have to rely on hunting and gathering to survive.

“Farming” soon replaced “spear-throwing” as the most popular skill on LinkedIn at the time. (Editor’s note: Aspects of that previous statement may not be 100% historically accurate.)

But as populations began growing around these steady food supplies, not everyone could be a farmer, and people who weren’t farmers needed stuff to do, apparently. That’s when job specialization started to take off.

For the first time ever, people began to have individual jobs. In addition to farmers, there were clay pot makers, builders, carpenters, soldiers, and so on.

For the first time ever, you could go up to someone and ask, “What do you do for a living?” and the answer would be something other than: “Survive.”

This is, arguably, the time when a person’s work became more clearly aligned with a person’s identity. And when the distinction between “work time” and “leisure time” became more pronounced.

350 B.C.

Aristotle first explores the notion of balancing work and leisure in his works Nicomachean Ethics and Politics. Here’s a quote from the latter:

The whole of life is further divided into two parts, business and leisure, war and peace, and of actions some aim at what is necessary and useful, and some at what is honorable. And the preference given to one or the other class of actions must necessarily be like the preference given to one or other part of the soul and its actions over the other; there must be war for the sake of peace, business for the sake of leisure, things useful and necessary for the sake of things honorable.

Ultimately, however, Aristotle’s interpretation of leisure wan’t a very egalitarian one. He contended that the majority of people worked not for the sake of their own leisure, but so that a minority of educated people could enjoy it and thus have time to devote themselves to “higher” pursuits.

As Italian philosopher Adriano Tilgher noted in his 1931 book, Work: What It Has Meant to Men Through the Ages, Aristotle’s advice for achieving a good or moral life was to “have the hard, troublesome work of transforming raw material for the satisfaction of our needs done by a part – the majority – of men, in order that the minority, the elite, might engage in pure exercise of the mind – art, philosophy, politics.”

Working at this time (specifically manual labor) wasn’t something to be proud of. In fact, the Greek word for work, ponos, was derived from the Latin word, poena, which meant “sorrow.”

1536 A.D.

After centuries of people viewing work as essentially a necessary evil, the “work/life" scale began to tilt in the direction of work.

With the publication of Institutes of the Christian Religion in 1536, French theologian John Calvin helped create the concept that we know today as the “Protestant work ethic.”

While Calvin’s philosophy is quite complicated, here’s the gist: God has predetermined who’s going to heaven (and who’s not), and there’s really nothing you can do to change your outcome. However, there are outward signs of who God’s chosen or “elected” people are – and one of those signs: being successful in business.

In his oft-debated essay, “The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism,” German sociologist Max Weber argued that Calvin’s work led to the idea that fulfilling one’s worldly duties (a.k.a. working) was the best way to prove one’s faith.

Weber also argued that the notion of working translating to morality/godliness helped give rise to the concept of one’s work being a “calling,” or “…an obligation which the individual is supposed to feel and does feel towards the content of his professional activity, no matter in what it consists…"

The Puritans, Quakers, and other Protestant groups who would eventually settle in the Americas brought this Calvinist philosophy with them to the New World.

As researcher Roger B. Hill noted in his essay, “Historical Context of the Work Ethic“:

"From their viewpoint, the moral life was one of hard work and determination, and they approached the task of building a new world in the wilderness as an opportunity to prove their own moral worth.”

1764

It’s difficult (if not impossible) to pinpoint the start of the Industrial Revolution, but 1764 seems like as good a year as any. That’s the year James Hargreaves invented the spinning jenny, a machine that allowed textile workers to spin multiple spools of thread at once.

More technological innovations were to follow, one of the most significant of which was James Watt’s steam engine of the 1770s. This invention would go on to power trains, ships, and industrial machinery.

As the world became more industrialized, the amount of hours people spent working began to increase. By the mid-nineteenth century (i.e., around 1850), the average full-time worker in Britain clocked in more than 3,000 work hours per year.

Disclaimer: That 3,000-hour figure, as well as the rest of the data depicted in the graph below, represent the low estimate. (Some researchers think that mid-nineteenth century laborers could have worked as much as 4,500 hours per year.)

However, from the mid-nineteenth century onward, the work/leisure scale began to tip back towards the side of leisure. As John T. Haworth and A. J. Veal noted in their 2004 essay, ”Work and Leisure“:

Having reached a peak in the mid-nineteenth century, working hours began to fall substantially, as a result, initially, of restrictions on working hours for women and children, followed by the campaign for the eight-hour working day for all, the move to the five-and-a-half-day and then the five-day working week and the advent of paid annual holiday entitlements. As a result, the typical working year for full-time employed workers fell to less than 2,000 hours in the post-Second World War era.

1986

This year marks the first published appearance of the term “work/life balance” (or to get technical, the term “work-and-life balance”) in the United States.* Prior to 1986, the concept was typically known as “work/leisure” or “work-leisure” balance.

*Wikipedia asserts that the term “work-life balance” was first used in the UK in the late 1970s, but I couldn’t verify the source.

Here’s the passage from the article – “Time to diversify your ‘life portfolio’?” (Industry Week, November 10, 1986) – where the term first appeared:

A Minneapolis consultant and author, Dick [Leider] paints a picture of managers struggling to capture a mythical thing called “balance” – a proportioning of their lives with sufficient weight on professional activities, but with a healthy counterweight of family and personal interests.

“It used to be that work-and-life balance was a boutique issue,” he says. “You know, something that would be great to worry about whenever – and if – one had some free time. But imbalance is killing people!”

The author of that article, Tom Brown, used the term again in 1988 (but this time dropped the “and”). Here’s the passage:

"A model employee is [one] who demonstrates a healthy work-life balance. In every company I know, the workaholic is alive – and sick."

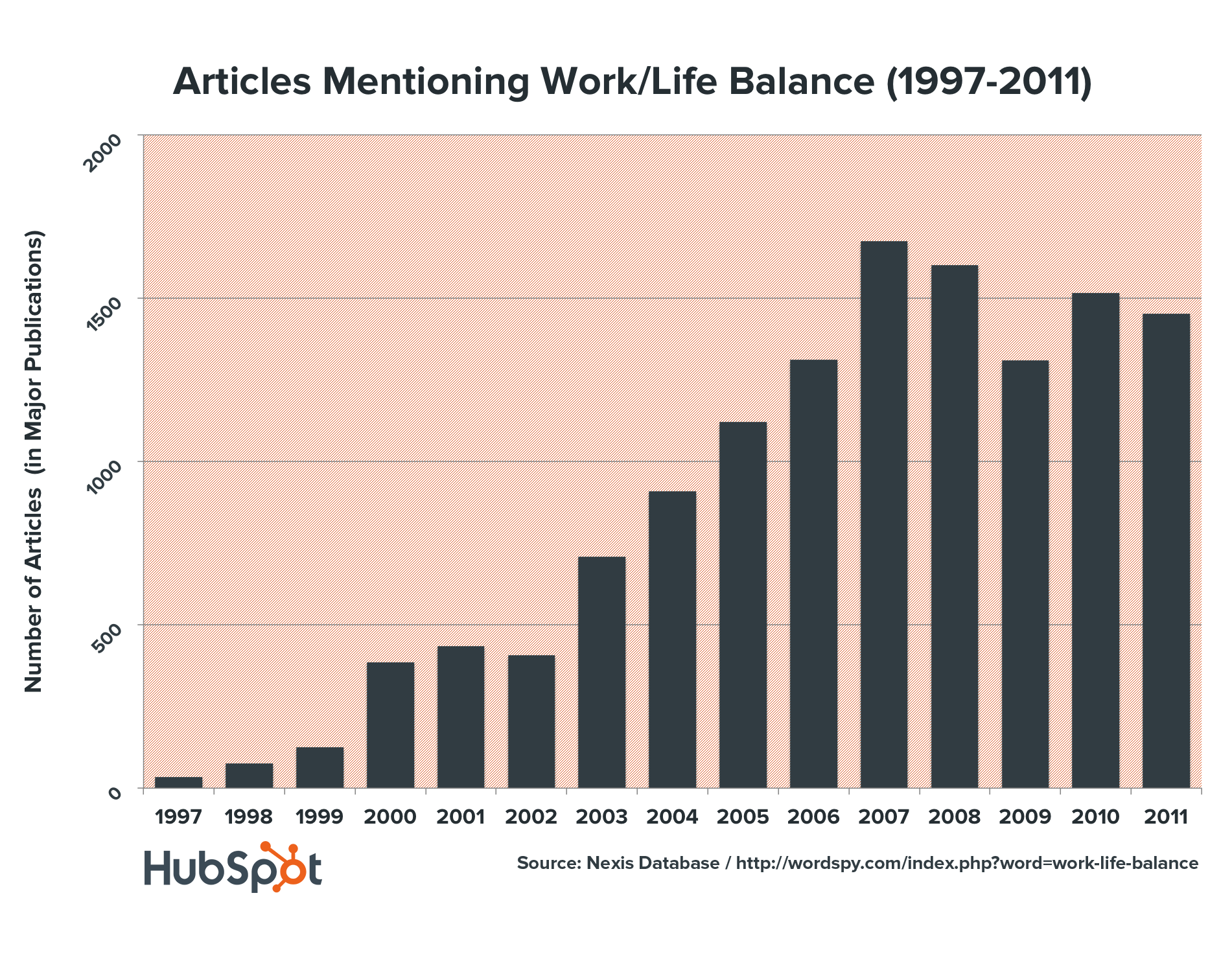

Between 1986 and 1996, the term “work/life balance” was only used in 32 articles published in major publications. Then, over the next few years, usage started to take off.

So, what caused this shift in terminology? How did we go from balancing work with leisure, to balancing work with our lives? Let’s explore some possible explanations.

The Reagan Effect

Perhaps the semantic change from “work/leisure” to “work/life" had something to do with the cultural and political environment of the 1980s. For example, the Reagan presidency (1981-1989) carried a strong pro-business, pro-individualism message. The success of the country became inexorably linked to the success of the country’s businesses. But at the same time, it was a strong individual work ethic, or the desire to better one’s own life, that seemed to be at the core of President Reagan’s philosophy.

Higher productivity, a larger gross national product, a healthy Dow Jones average–they are our goals and are worthy ones. But our real concerns are not statistical goals or material gain. We want to expand personal freedom, to renew the American dream for every American. We seek to restore opportunity and reward, to value again personal achievement and individual excellence. We seek to rely on the ingenuity and energy of the American people to better their own lives and those of millions of others around the world.

There’s something very Calvinistic about this emphasis on individual achievement. And when you consider this next quote from President Reagan, the parallels become even more clear: “The American dream is not that every man must be level with every other man. The American dream is that every man must be free to become whatever God intends he should become.”

So, could it be that shifting cultural and political attitudes put a greater emphasis on work, thus shifting the conversation from balancing work with leisure to balancing work with, well, everything else? Possibly. But what’s more likely is that this was just one piece of the puzzle.

Let’s explore some other potential pieces …

The “Maximizing Shareholder Value” Effect

Prior to 1980, “maximizing shareholder value” was a novel concept – not the popular corporate slogan it is today.

As journalist Jia Lynn Yang noted in a 2013 Washington Post article, "The belief that shareholders come first is not codified by statute. Rather, it was introduced by a handful of free-market academics in the 1970s and then picked up by business leaders and the media until it became an oft-repeated mantra in the corporate world.”

Even as early as 1998, researchers were looking back to the 1980s and saying, “Whoa, there was a big change here.”

Consider this passage from researcher Steven Neil Kaplan of the University of Chicago Booth School of Business:

Before 1980, corporate governance in the United States was very different from today. Executives held modest amounts of stock and options in their companies. Top executives and their incentives were more focused on traditional performance measures such as sales or earnings growth. Boards of directors were not particularly active and shareholders were relatively passive.

It’s possible that this shift in corporate governance is what led to the reframing of the conversation around balancing work and leisure activities. With a stronger emphasis now being put on increasing the value of a business – rather than, say, making quality products or helping the community – the language needed to evolve to match this new objective.

Balancing work with leisure, after all, implied that work and leisure (i.e, the use of free time for enjoyment) were equals. But in this new corporate landscape where “maximizing shareholder value” and “solving for enterprise value (EV)” were paramount, giving equal consideration to work and leisure seemed at odds with corporate goals.

The Technology Effect

Here’s a final explanation for why “work/leisure” balance became “work/life" balance: the terminology evolved with technology.

Cell phones, email, instant messaging … most of these technologies emerged in the 1970s and 1980s and then rose to prominence in the 1990s and 2000s. Increased adoption of these communication tools made it easier for workers to stay connected to their work, even when they weren’t physically in the office.

So, perhaps the decline of the “work/leisure” terminology is due to the fact that work now has the ability to infiltrate leisure time. There can no longer be a clear distinction between the two.

You can check work email while sitting on the beach. You can take a work call on your cell phone at your kid’s soccer game. You can send and receive instant messages with colleagues during a family dinner.

With work now capable of invading our lives at every turn (thanks to technology), “work/life” balance is simply a more accurate way to describe the concept once known as “work/leisure” balance.

What Does “Work/Life” Balance Mean Today?

In today’s technologically connected corporate world, where uninterrupted leisure time is difficult (if not impossible) to come by, is the concept of “work/life" balance dead? Does the term have any real meaning at all?

When we approach the question quantitatively, we can see that yes – of course – most people around the world devote a certain portion of their time to work and a certain portion of their time to leisure. So there is a balancing act happening here.

And as the graphs below help illustrate, this balancing act varies greatly depending on where you live:

When we approach the “Is work/life balance dead?” question from a qualitative perspective, however, the findings (not surprisingly) are a bit more ambiguous.

“In most corporate circles, [work/life balance is] the sort of phrase that gives hard-charging managers the hives, bringing to mind yoga-infused, candlelit meditation sessions and – more frustratingly – rows of empty office cubicles,” noted authors Claire Shipman and Katty Kay in a 2009 Time article.

"So, what if we renamed work-life balance?” they continued. "Let’s call it something more masculine and appealing, something like … um … Make More Money.”

The takeaway here is that the modern concept of "work/life” balance has taken on – to use the authors’ language – a “nutty-crunchy” connotation. Some managers hear the term and immediately conjure up images of care-free employees taking extended hacky sack breaks, or employees piling into VW buses for last-minute, week-long road trips to Burning Man.

But at the end of the day, having flexibility in the workplace, and being able to balance work activities with non-work activities, can end up making employees more productive. And that’s good for business.

"Flexibility is no longer a favor to be handed out like candy at a children’s birthday party; it’s a compelling business strategy.” Ship and Kay argued. "So we need to get rid of the nutty-crunchy moral component of the work-life balance and make a business case for it.”

But … What About Your Life?

So, we’ve established that “work/life” balance, despite its granola-esque reputation, has the potential to be beneficial for business. But is it beneficial for the other side of the “work/life” equation … you know, your life?

For University of Michigan researcher Paula J. Caproni, the language surrounding “work/life” balance – like developing a vision, having a clear focus, executing an action plan, and identifying central priorities – is eerily similar to the language used when describing bureaucratic organizations.

“Statements such as these are equally at home in the boardroom of a Fortune 100 company or in any MBA strategy classroom and reflect the individualism, goal focus, achievement orientation, and instrumental rationality devoid of emotion that is fundamental to modern bureaucratic thought and action,” she noted in a 1997 article for the Journal of Applied Behavioral Sciences.

Caproni continued, “Is this really the language we want to use to guide our personal lives?”

Ultimately, Caproni found two primary problems with striving for "work/life” balance. The first is that dedicating our lives to a solitary goal (e.g., achieving “work/life” balance) may “lead us down the same path we are trying to get off, directing us to overplan our lives at the expense of living our lives.“

In other words, we could become so obsessed with “balancing” events and interactions in our lives that our lives could lose all spontaneity; we could end up simply “going through the motions” of life instead of truly living.

This quote from British philosopher Alan Watts helps illustrate that notion:

Because we thought of life by analogy with a journey – with a pilgrimage. Which had a serious purpose at the end and the thing was to get to that end; success or whatever it is or maybe heaven after you’re dead. But we missed the point the whole way along. It was a musical thing and you were supposed to sing and to dance while the music was being played.

Caproni’s other main problem with “work/life” balance, which piggybacks off the first, is that taking such a strategic approach to life ignores the inherent unpredictability and dynamism of life: Unplanned events can and will happen, which means all of that extensive planning and manipulating you do for the sake of “balance” could end up being pointless.

“A strategic orientation to life underestimates the degree to which life is, and probably should be, deeply emotional, haphazard, and uncontrollable,” Caproni wrote. “Balance, perhaps thankfully, may be beyond our reach."

And if "work/life” balance is, in fact, unreachable, striving for it sets us up for “continuous frustration.“

Caproni also points out that striving for "work/life” balance implies that we have some sort of imbalance that we’re trying to cure; some deficiency that we need to correct.

This line of reasoning can lead us to develop “idealized images” of ourselves; unrealistic representations of what we think we should be. And while striving for self-improvement is typically considered a good thing, it can ultimately be detrimental if that “idealized image” of ourselves has no basis in reality.

If you set impossible expectations for yourself, you’ll never meet or exceed them. And while that statement doesn’t make for a great motivational poster, it can help protect you from feeling like a failure, or like you’re coming up short (when in reality, you are not the problem – your unrealistic expectations are).

On the Other Hand …

If striving for some idealistic sense of balance, even if it is unattainable, motivates you and makes you happier and more productive … who’s to say you shouldn’t keep on striving for it?

If those “work/life” balance tips and tricks you’ve been reading are actually helpful, stick with ‘em! In the immortal words of the Isley Brothers: “It’s your thing / Do what you wanna do.”

And while over-planning and being too goal-oriented can have their consequences, there’s certainly nothing wrong with being mindful of how you’re living your life and spending your time (both of which – life and time – are rather precious commodities, most of us would agree).

As Groysberg and Abrahams noted, “…by making deliberate choices about which opportunities they’ll pursue and which they’ll decline, rather than simply reacting to emergencies, leaders can and do engage meaningfully with work, family, and community.“

I think the danger comes when this “deliberate choice-making” (to paraphrase) becomes your modus operandi, or sole operating principle. It reduces life to a series of decisions, whereas one might argue that life is instead best viewed, and enjoyed, as a series of experiences.

In Conclusion

If you’ve recently boarded the “work/life” balance train and don’t like where it’s heading, you shouldn’t be afraid to jump off. While this approach proves effective for many, it’s not a science.

Instead of striving for “work/life” balance, you may want to consider simply striving for a good life. Instead of thinking of “work" and “life" as equals, make “life” your priority, and acknowledge that what you do for work is simply a part of that life.

A final (and potentially controversial) piece of advice for those struggling with “work/life” balance: Forget about having your work be your calling or your passion. It’s great if those two things – your work and your passion – do align, but ultimately, you can always find your passion outside of the office.

And as it turns out, that’s exactly what Caproni did: “I gave up the notion that I should find passion in my work,” she wrote, “and instead looked to where I could make the greatest contribution for the most people and sought to keep passion in the home.”

At the end of the day, there’s no rule that says you must derive some deeper meaning out of your work in order to be a good worker or to have a good life. My recommendation: Be passionate about your life first, then figure out how your work fits into it.

from HubSpot Marketing Blog http://ift.tt/1HfzK6V

from Tumblr http://ift.tt/1IISP73

No comments:

Post a Comment